“An unfathomable light fills the entire orb of the earth.

Ringing powerfully through and through is the most highly desired assurance”. J.S.Bach, Cantata no 125, With Peace and Joy I Depart.

While he was recovering in hospital from a heart attack, Carl Jung had a series of visionary experiences that have become widely known from the account in his autobiography: “it seemed to me that I was high up in space. Far below I saw the globe of the Earth, bathed in a gloriously blue light. I saw the deep blue sea and the continents. Far below my feet lay Ceylon, and in the distance ahead of me the subcontinent of India. My field of vision did not include the whole Earth, but its global shape was plainly distinguishable and its outlines shone with a silvery gleam through that wonderful blue light. In many places the globe seemed coloured, or spotted dark green like oxidized silver.” This was almost twenty five years before astronauts sent back images of Earthrise from the Moon.

Jung then became aware of a huge black stone floating nearby, reminiscent of some rocks he had seen on the coast of the Bay of Bengal in which temples has been carved. A Hindu man was waiting for him at the entrance to just such a temple. “As I approached the steps leading up to the entrance into the rock, a strange thing happened: I had the feeling that everything was being sloughed away; everything I aimed at or wished for or thought, the whole phantasmagoria of earthly existence, fell away or was stripped from me – an extremely painful process. Nevertheless something remained; it was as if I now carried along with me everything I had ever experienced or done, everything that had happened around me. I might also say: it was with me, and I was it. I consisted of all that, so to speak. I consisted of my own history and I felt with great certainty: this is what I am. I am this bundle of what has been and what has been accomplished“.(1).

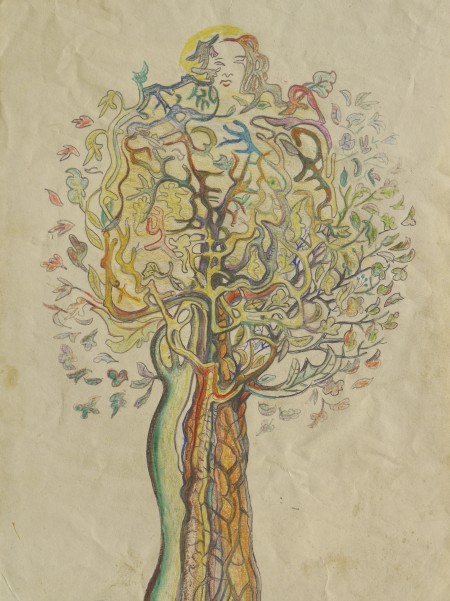

After many years’ work he had just completed Psychology and Alchemy, and had been meditating on alchemical symbolism. It is perhaps not surprising then that he saw, or was shown, a huge black stone, or lapis. The epilogue to Psychology and Alchemy concludes with the prescient assertion that ‘mysterious life-processes’ pose riddles that can’t be solved by reason alone. We must engage with direct experience. ‘As the alchemists themselves warned us: “Rumpite libros, ne corda vestra rumpantur” -Rend the books, lest your heart be rent asunder’.

During the N.D.E vision Jung met his doctor in ‘primal form’. Shortly after this he became furious with the doctor’s insistence that he return to the ‘prison’ of earthly life, and frustrated by his refusal to talk about their recent otherworldly meeting. He was also seized by a premonitory conviction that his own life was about to be exchanged for that of the doctor. Then, on the day he was finally allowed to sit up in bed the doctor came down with a fever that proved fatal.

After this he experienced a sequence of indescribably beautiful and intense visions of otherworldly weddings, including the mystic marriage between ‘All-father Zeus and Hera’.

Despite his marked reluctance to return to the ‘box system’ of Earthly life, Jung tells us that: “After the illness a fruitful period of work began for me. A good many of my principal works were written only then … I surrendered myself to the current of my thoughts. Thus one problem after the other revealed itself to me and took shape.”

In subsequent writings he discussed the alchemical notion of scintillae, or sparks from the light of nature -‘seeds of light broadcast in the chaos’ […] ‘dispersed or sprinkled in and throughout the structure of the great world into all fruits of the elements everywhere’. I particularly like Cornelius Agrippa von Nettleheim’s observation that from this “luminositas sensus naturae”, ‘gleams of prophecy come down to the four footed beasts, the birds, and other living creatures, enabling them to foretell future things’.(2) Many N.D.E. experiencers describe meeting beings of light (sometimes percieved as angels) that may lead or follow them, and take their pain away.

Jung’s account raises many questions -about the effect of cultural assumptions, emotional states, and spiritual practice, as well as about the nature of other dimensions or worlds and their inhabitants. His perception of earthly life as a ‘prison’, for example, seems a rather extreme expression of the inevitable tension between otherworldly ecstasy and remembered pain in this world. Perhaps he was influenced by the longstanding devaluation of material existence (and of women as agents of incarnation) in Western philosophy and transcendental religion? This prejudice, which feminist theorists such as Val Plumwood and Grace Jantzen have traced back to Plato -whose Story of Er is regarded as one of the first recognisable ‘N.D.E’ accounts- reached its apogee in gnosticism, and is apparent where alchemy becomes a quest to liberate light ‘imprisoned’ in matter.

N.D.E. studies consistently find that people typically return with a deepened and broadened spiritual sensibility. Some people have abandoned rigid religious views after meeting spiritual figures or deities from traditions other than their own. On the other hand many N.D.E’rs don’t associate the ‘beings of light’ they meet with any religious tradition. Jung’s account is the only one I’ve seen to date in which Pagan deities appear. His visions differ from the classic ‘N.D.E’ in that they continued during an almost three week period of tenuous recovery, but were typically pluralistic (as well as reflective of his worldview) since he also encountered figures from Hindu, Jewish Kabbalistic, and Christian traditions.

Unfortunately much of the N.D.E. literature is framed in dualistic New Age or Christian terms. Even Kenneth Ring, an American psychologist, talks about ‘black uncertainty’ and the ‘blackest moments’ of the twentieth Century, and refers to ‘the Light’ coming to show us our evolutionary way forward.(3) Against this we might mention various positive references to fecund blackness in alchemy -‘the black earth in which the gold of the lapis is sown like the grain of wheat’, or ‘the exeeding precious stone proclaims: “I beget the light, but the darkness too is of my nature” ‘.(4)

My take on this is that we need to recognise the difference between duality and dualism. Clearly, there needs to be debate about how ‘N.D.E’-like experiences are framed, and how they can be recruited into dominant religious discourse. Some of the frightening ‘N.D.E’s that have been somewhat marginalised within the dualistic literature may be akin to ‘the perilous adventure of the night sea journey’, shamanic initiation, or the ordeal of the deceased in the Bardo realm of Tibetan lore. Jung, did, after all, describe the ‘life review’-like element of his visionary experience as ‘an extremely painful process’, and felt depressed about the need to return.

Integration.

A recent research study involving fifty participants from an American town focussed on responding to the often problematic impact and after effects of N.D.E-like experiences. Suzanne Gordon situated her research in the context of ‘escalating social and ecological crises and an in-progress paradigm-shift away from the still-official Newtonian/Cartesian material world view of Western culture’ [towards] a (re)emergent sacred worldview more comparable to diverse indigenous knowledge systems. She argues that the marginalisation faced by people who have had Spiritually Transformative Experiences (not just N.D.E’s) is comparable to discrimination on the basis of sexuality, and has been instrumental in setting up an organisation that aims to listen to the stories of experts-by-experience, de-medicalise spiritual/visionary experience, educate professionals, and establish peer support groups.(5)

Near Death Experiencers tend to become more altruistic and compassionate, and have an increased appreciation of life. They may feel a greater concern for the ecological health of the planet and some acquire acute psychic sensitivity and/or healing abilities. The process of re-integration within an uncomprehending mainstream is often challenging however. Only three of Gordon’s fifty participants had little difficulty with integration -two of whom were the only two African American participants in her project. One of these women said that her family ‘talk to dead people all the time’. The only difference her N.D.E. had made was that her ‘windows were open a little more’, and she now had no fear of death.

To be continued …

B.T. 24nd February 2017.

Sources.

(1) Carl Jung, Memories, Dreams, Reflections, Knopf Doubleday 2011, and a longer extract here.

(2) Carl Jung, On the Nature of the Psyche, Routledge Classics, 2001, citing Khunrath and von Nettleheim, and Psychology and Alchemy, Routledge Kegan and Paul 1980 (first published 1944).

(3) For example his chapter in Lee W. Bailey and Jenny Yates, The Near Death Experience, A Reader, Routledge, 2013.

(4) Carl Jung, Pyschology and Alchemy, Routledge Kegan and Paul 1980 (first published 1944)

(5) Suzanne Gordon, Field Notes from the Light, PhD thesis, University of Maryland, 2007 and see the webiste of the American Centre for the Integration of Spirituality.