A research study based on interviews with nurses, doctors, and carers in two hospices and one nursing home in London found that profoundly meaningful ‘end of life experiences’ were not uncommon. Peter Fenwick, Hilary Lovelace, and Sue Brayne, conclude that the subjective experiences of people who are dying, and phenomena that occur around death, need to be taken seriously if we are to develop best practice in spiritual end-of-life care.

Amongst the end-of-life experiences commonly reported are visions of deceased relatives (or friends) sitting on or next to the patient’s bed providing emotional warmth and comfort (64% and 54% in retrospective and prospective studies), visions of relatives or ‘religious figures’ who appear to ‘collect’ the dying person (62% and 48%), a sense of transitioning between this world and another reality (33% and 48%), dreams or visions in which the person feels comforted and prepared for death (62% and 50%), a sense of being called or pulled by someone or something (56% and 57%), the symbolic appearance of a significant bird, animal, or insect near the time of death (45% and 35%), light surrounding or near the dying person (often seen by therapists), relatives or friends being ‘visited’ by them at the time of death (55% and 48%), and synchronic occurances such as clocks stopping or lights coming on. The prevailing scientific view, however, has been that ELE’s, especially deathbed visions, ‘have no intrinsic value, and are either confusional or drug induced.'(1)

Although Peter Fenwick, a renowned neuropsychiatrist, is no critical or post- psychiatrist, he clearly realises the importance of taking what people say seriously, not least when many respondents feared they would be thought mad if they talked about their visions. His writings therefore cast some interesting light on an important but culturally neglected area of human experience. I’m reminded of the work of Marius Romme and Sandra Escher on voice hearing (which challenged the medicalisation of madness) and, to some extent, Stanislas Grof on perinatal and transpersonal experience (but see note 1).

In the first of two books (co-authored with his wife Elizabeth Fenwick, a writer on health issues) Peter Fenwick reviews some 350 responses to a questionnaire sent to people who responded to his media appearances. Although the main features described in Near Death Experiences -passing along a tunnel towards a welcoming and compassionate light, meeting beings of ‘light’, a momentary but somehow panoramic life review, coming to a barrier of some kind where a decision is made, and returning to the physical body- have become quite well known, only 2% of Fenwick’s respondents had previously heard of N.D.E’s. For most, their Near Death Experience was a spiritual awakening in a broad and universal sense.

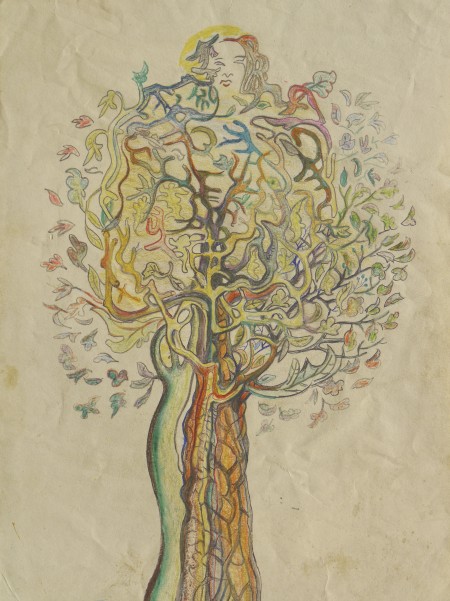

The accounts of N.D.E’s presented in this and other studies (cited here) do, nevertheless, show considerable individual and cultural variation. For example, American studies report many more appearances by Jesus and by angels, whilst a study of Indian experiences showed that most people there were collected by Yamraj, the messenger of the Hindu god of death, rather than by deceased relatives. Some Western individuals, however, met figures from Eastern cultures -and had their religious horizons broadened as a result. For one woman the welcoming presence was a tree.

Most of the accounts were intensely autobiographical, but a few people were ‘shown glimpses of the past or of the future on a more cosmic scale’. One man who could see Peterborough cathedral and small W’s of swans flying across the sky as he waited for an operation, but then suffered a coronory thrombosis followed by cardiac arrest and was rushed into Intensive Care, felt himself “become weightless several times and float up into the sky” where he joined the swans as a “very junior member of their family group”. During some of these flights he was aware that the cathedral had not been built yet. “It was as though the fens were in a primeval state”. He saw men in medieval dress punting on the great meres, and the cathedral being built. “I felt as if I had existed forever, my being and ‘soul’ had been this way before.” (Fenwick 1996 pp131-2)

Cultural variation could be taken to show that such experiences are socially constructed in much the same way as dreams, but of course, otherworlds might also be constructed in ways that make them familiar and welcoming – congruent with the expectations, needs, and understandings of new arrivals. Intriguingly, 38% of respondents met someone ‘on the other side’ who was still alive. Does this mean that their experiences were ‘just dreams’? Shortly after the death of her mother, a Japanese woman dreamt that she was standing in the middle of a river with her parents on either side. Her mother was beckoning her father to cross, but he didn’t. Although, in keeping with Japanese Buddhist symbolism, the barrier between worlds often takes the form of a river in Japanese N.D.E accounts, this woman had been brought up a Christian with no knowledge of Buddhism, and no recollection of hearing about the river symbolism. (we are not told whether she’d heard about the Styx though).

Given the intensely subjective and emotional nature of these experiences I was not entirely suprised to see that 78% of respondents were women.

In the Fenwicks’ second book, which reports findings from the study of London health professionals and carers, the concept of a journey emerges as a central theme. The other world which people visit has a quality of absolute reality, but in the case of ‘deathbed visions’ it is as though ‘this world and the other reality overlap, dissolving into each other so that both can be experienced at once’. (2008 p44) The dying person is rarely confused by this, is usually aware that not everyone can see what they can see, and may conduct separate simultaneous conversations with this-worldy and other-worldly visitors. Given the importance of sorting out unfinshed business, it’s interesting that many carers report that two or three days before a death a room often becomes extremely peaceful and dominated by feelings of love, as though the process of death somehow sets up conditions that facilitate the resolution of personal conflict. For me this (along with various phenomena mentioned in other accounts) raises questions about the agency and power of other-worldly people vis-a-vis this worldly affairs.

There are fairly brief discussions of the Tibetan Book of the Dead, mythological themes, Jungian archetypes, quantum entanglement, and the notion of extended and inter-connected mind. I couldn’t help noticing some tension between two authorial voices -within Peter Fenwick I suspect. One regards ghosts and mediumship as ‘tiger country for scientists’, writes that most of us ‘cling to this pale ghost … like a child with its comfort blanket’, persists in referring to visions as hallucinations even where the person is lucid (and despite instances where a vision is shared by other people), and eagerly anticipates ‘a body of homespun Western mystics becoming available for study’, whilst another is open-mindedly empathetic and, for example, regards co-incidence as a simplistic explanation for many of these phenomena. I was also concerned that the authors’ perspective veered towards over-valuing the transcendental. Their work, nonetheless, constitutes a significant challenge to cultural amnesia, and to insititutional resistance against respecting intimate subjective experience.

I’ll close by quoting from a contribution from a woman describing her sister’s death: “I saw a fast moving ‘Willo-the-wisp’ appear to leave her body from the side of her mouth on the right. The shock and beauty of it made me gasp. It appeared like a fluid or gaseous diamond, pristine, sparkly, and pure, akin to the view from above of an eddy in the clearest pool you can imagine.”

B.T 26/4/15

Note 1: Unlike Peter Fenwick, Stanislas Grof developed an intensive ‘therapeutic’ method, inclduing controversial experimental work with LSD.

Sources:

(1) Fenwick, P et al, (2009) Comfort for the Dying: five year retrospective and one year prospective studies of end of life experiences. Archives of Gerontology and Geriatrics, 2009. doi: 10.1016/j.archger.2009.10.004

Fenwick, P (2004) Dying, a Spiritual Experience as shown by Near Death Experiences and Deathbed Visions. http://www.rcpsych.ac.uk/PDF/PFenwickNearDeath.pdf (accessed 17/3/15).

Fenwick, P and Fenwick, E (1996) The Truth in the Light, An Investigation of over 300 Near-Death Experiences, White Crow Books.

Fenwick, P and Fenwick, E. (2008) The Art of Dying, London, Bloomsbury.

Fenwick P. (2012) Dr Peter Fenwick Discusses Dying, Death, and Survivial, Interview by White Crow Books: